Storm and Stress

Gustav Mahler's Tragic Symphony, and Our Own

I spent the summer of 1992 living in Morningside Heights. I would often read entire books on shady spots on the Columbia campus outside Hamilton Hall. The statue of Hamilton looked over us. He had fought in the Revolutionary War and returned to study. I knew that the same building had been occupied in the tumult of ‘68, but that was five years before I was born. All was relatively tranquillo, though reminders of war were everywhere. I would often search for ideal spots to read—a clean, well-lighted place, not too much to ask for, I thought. I was 19. The Cold War was ending. What rough beast was next? I was excited to vote for the first time, and The Bill Clinton Show never failed to entertain. But books were the priority for my brain. I knew that apocalypse was possible, but the Cold War had ended, the Gulf War was over in under a week. The draft was over the month I was born.

There was an entire Tower Records devoted to classical music, and there was a guy who worked there who seemed to know everything. He told me what to buy and what to avoid, and I trusted him. There was a Sony Budget Classics recording of Mahler’s 6th with Cleveland conducted by George Szell. It’s the only Mahler’s 6th I would ever need. Sarah Lawrence had a music library, in the building where I would eventually get married. I went through all the Mahler’s 6ths on vinyl, and he was right. The Bernstein one sounded soft, and the Solti one was closer, but still not quite Szell. That guy at Tower Records was onto something.

It is now 2024, and the world has ended a few times over. A friend gave me a box seat ticket for Mahler’s 6th with Sir Simon Rattle, one of the great Mahler conductors still striding the stage. The Columbia campus was six subway stops ahead, and a little further for CCNY. The world is tearing itself apart in the Middle East, and students are enraged, and I get it. All this suffering of the vulnerable, this ceaseless perishing—intolerable! Who knows what is getting filtered through the news, but when I hear undergraduates say that they cannot get to the library without being harassed—when the administration is suggesting they stay in their dorms—I remember sharing their priorities, and it makes me want to weep. I wanted to hide with my beloved in the stacks and listen to music in my dorm room, and when we listened to Mahler, we went through the tsuris to prepare us for our own. We thought we knew what pity and fear was; we had no idea. I was irritated by the loud students who were just enjoying their youth. I was reading about sturm und drang already. I didn’t feel like experiencing it in real time. I wanted to read and write and fall in love and follow Stephen Dedalus’s journey to forge in the smithy of his soul.

“Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”

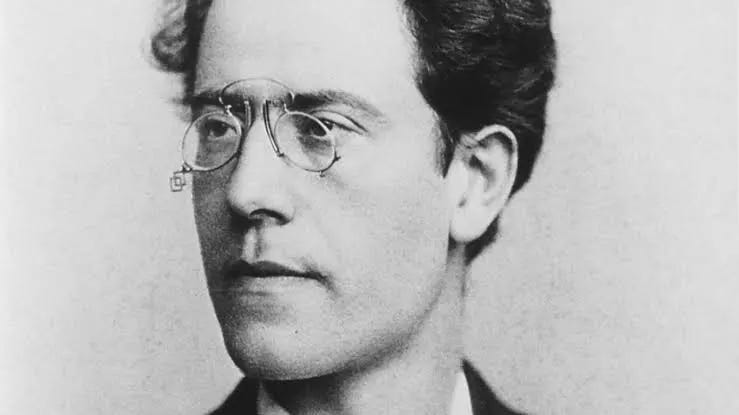

Real life is a mess. Our bodies are falling apart. Even if we aren’t feeling it right now, we will. Mahler died at 51—the same age I am right now. And every one of those symphonies did not come effortlessly. You can hear the pangs, and that is part of the pleasure, if you love Mahler, as I do. I watched Rattle, wearing not a tux but a black outfit that was made for the heavy duty physical activity that he, almost 70, was about to do. All my years at Carnegie Hall have been in either press seats or student rush tickets. This was my first time in a box, and I could see Rattle looking at the Bavarian Radio Orchestra for a long time. He was calculating the whole thing before he started. He was looking at the entire orchestra as if to say, “I’ve got you.” He had better be arrogant. That’s his job.