In the fall of 1990, I found myself at the Majestic Theatre in Dallas, onstage with the members of the Modern Jazz Quartet—John Lewis, Percy Heath, Milt Jackson, Connie Kay. This was a perk of playing keybs in the jazz band at the Booker T. Washington High School for Performing and Visual Arts. We didn’t just get tix—we got the VIP treatment, chatting up legends after the gig. I was in awe. Lewis’s “Django” was a staple of our jazz combo, and also my sets as a restaurant pianist. It is, without question, one of the great American melodies, and he wrote many less well known peers to it. I wanted to live up to that melody then, and I know it will always be beyond me, yet me. “Django” was something to revere. I was haunted by its beauty, and it made me think of the Gypsy guitarist it was named for and his wild spirit, though the song really evoked Django playing a ballad, which was still wild, just slowed down. It was a restrained and exquisite tribute to an unrestrained bandit of the guitar, a guy who did more with three good fingers than almost anyone else could do with a full hand. He barely knew how to read and write, but he was a wild genius. “Django” has been compared to a movement in Mendelssohn’s Octet, but, if you invited the real Django over, he’d steal your silverware if he could.

But where, as a 17-year-old, could I start with “Django”? The thing that I had to talk about was an album that had Connie Kay on drums, an album that seemed to fit every occasion.

I kissed you on the lips once more

And we said goodbye just adoring the nighttime

Yeah, that's the right time

To feel the way that young lovers do

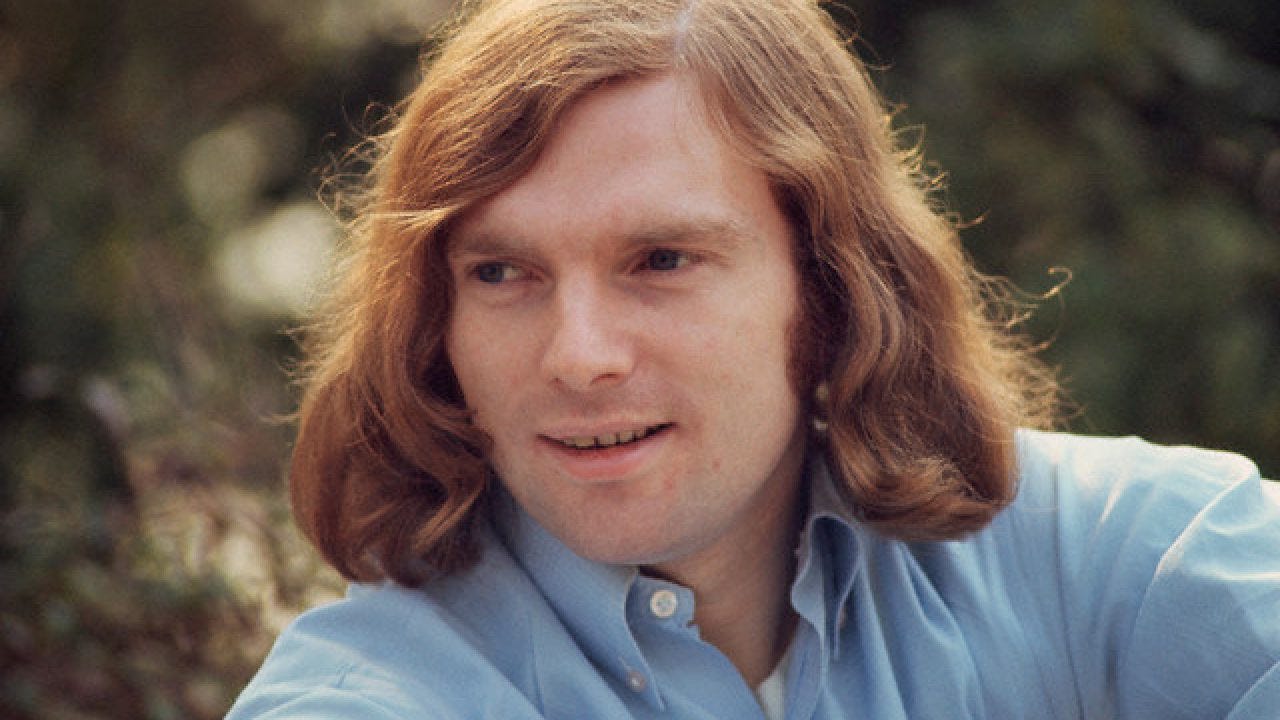

That one. It sounded like what it was, except in the way that a Degas painting looked like a naked body. It was exalted. It was sublime. The rhythms were unmistakable. The voice of young Van Morrison could capture everything we were feeling. Into the mystic. Exactly.

So Connie Kay played those beautiful drum parts, and I wanted to get something—anything—about that session, that music. I was so young. I thought that a gig from 1968 wasn’t filtered through anything else that led up to 1990. And there’s a part of me that still wants to feel this way as I still talk to musicians about the old archive. You never know. But here’s all I got.

“Hey, Connie. This kid says you recorded a record with this Irish cat Van Morrison in 1968.”

“Who?”

That was it. I thought that musicians who recorded rock star sessions for Warner Bros were well compensated and would remember the gig. Plus it’s Astral Weeks. There is nothing quite like it. It’s inspiration from start to finish, then it starts right over. I’m listening to “Cypress Avenue” right now and I want to cry. I remember being moved as a teenager and being moved still, though I know things that would have busted that kid’s brains out. But the feeling still remains. Those bass lines from Richard Davis—he who kept time for Dolphy and Coltrane—make the act of maintaining the pulse sensuous and free, while still maintaining the pulse. When people are unhappy, they say that tomorrow creeps this petty pace. When they are happy, time flies. Here, it soars. I recently interviewed the great Ron Carter about the bass—keeping time while making it sacred, sensuous, really anything it could be. He said he was just trying to find the right notes, aware of the guy at the bar shaking ice, trying not to think about anything that might steer him off course.

There was no YouTube in 1990, so I didn’t get to see all that footage of Van Morrison being grumpy. He had good reason. When he recorded Astral Weeks, he already had hits—”Gloria,” “Here Comes The Night,” “Brown Eyed Girl,” but he was dead broke. Of all the people that got screwed in the music business, he really got screwed. That’s probably why Connie Kay didn’t remember that gig. That young Irish hippie thought he was the second coming of Yeats, but he had very little to spend on this thing of beauty. Eventually, Van Morrison made money, and he’s even Sir Van now, but he’s not getting older, he’s getting bitter. He doesn’t even think Astral Weeks was that big of a deal.

The title track of Astral Weeks was said to be improvised. Every time it starts, it transports me. Goosebumps. Falling in love. Possibility. Transfiguration. “To be born again.” Most of the song is about being born again, though there’s this reference to “the look of avarice” and “talking to Huddie Ledbetter.” Someone is ripping off Leadbelly. The are sticking a microphone in that prison cell and getting “Goodnight, Irene” for The Weavers. Van is getting ripped off, so it’s hard to imagine thinking of himself as complicit. (Alan Lomax, who made those prison recordings of Leadbelly, wasn’t complicit, either. He was a folklorist spreading the word.). Sure, Van sounds more like a black soul singer than an Irish tenor, but he doesn’t sound like either. He’s nothing but a stranger in this world. He’s broke and brimming and has a girlfriend named Janet Planet.

In the voice of Nat Cole, I love Astral Weeks for sentimental reasons. Van the Man performed it live in 2008, but then said he just did it to finally reclaim the rights to the record. We don’t have the rights to the record, either. But we feel that it is ours. The musicians who tour with Van are on a tightrope. They never know if they are getting fired from night to night. One night, before a show, he turned to the piano player and said, “No sevenths.”

It’s a good thing he didn’t have this policy on Astral Weeks.

Every member of the MJQ died a long time ago, and I was lucky to see each of them when I could. When I was 17, I had a very good year. Astral Weeks played over and over again. And I thought the musicians were playing just for me and whoever I brought with me.

Shortly before recording “Astral Weeks,” Van was getting into the album’s groove when he recorded “TB Sheets.”

The cool room, Lord, is a fool's room

The cool room, Lord, Lord, is a fool's room

And I can almost smell your T.B. sheets

I can almost smell your T.B. sheets, T.B.

He was so young, but could catch a whiff of death in the streets of Belfast. Van Morrison would not catch his death. He would keep going. When he got knighted, he had his hat and sunglasses off and even removed the attitude for the occasion. Let him be celebrated. If he wants to be a prick, it’s his business. He made Astral Weeks. And that one night in Dallas, I, a blushing ephebe, could be told by its drummer the word “Who?” Ain’t nothing but a stranger in this world.

As usual your writing made me run to re-listen....

Love his music (especially astral weeks and moondance) but the attitude has diminished it for me. Love your musings