Sounded Like Applause

Joni Mitchell's Walden Woods

As we celebrate the album renaissance of 1972—50 years ago—we begin with Joni Mitchell’s For the Roses. It was the album that followed Blue, and is, in some ways, even more demanding. It is the Joni album that was inducted into the National Registry of the Library of Congress, who asked me to write something for the occasion. Call me at the station, the lines are open.

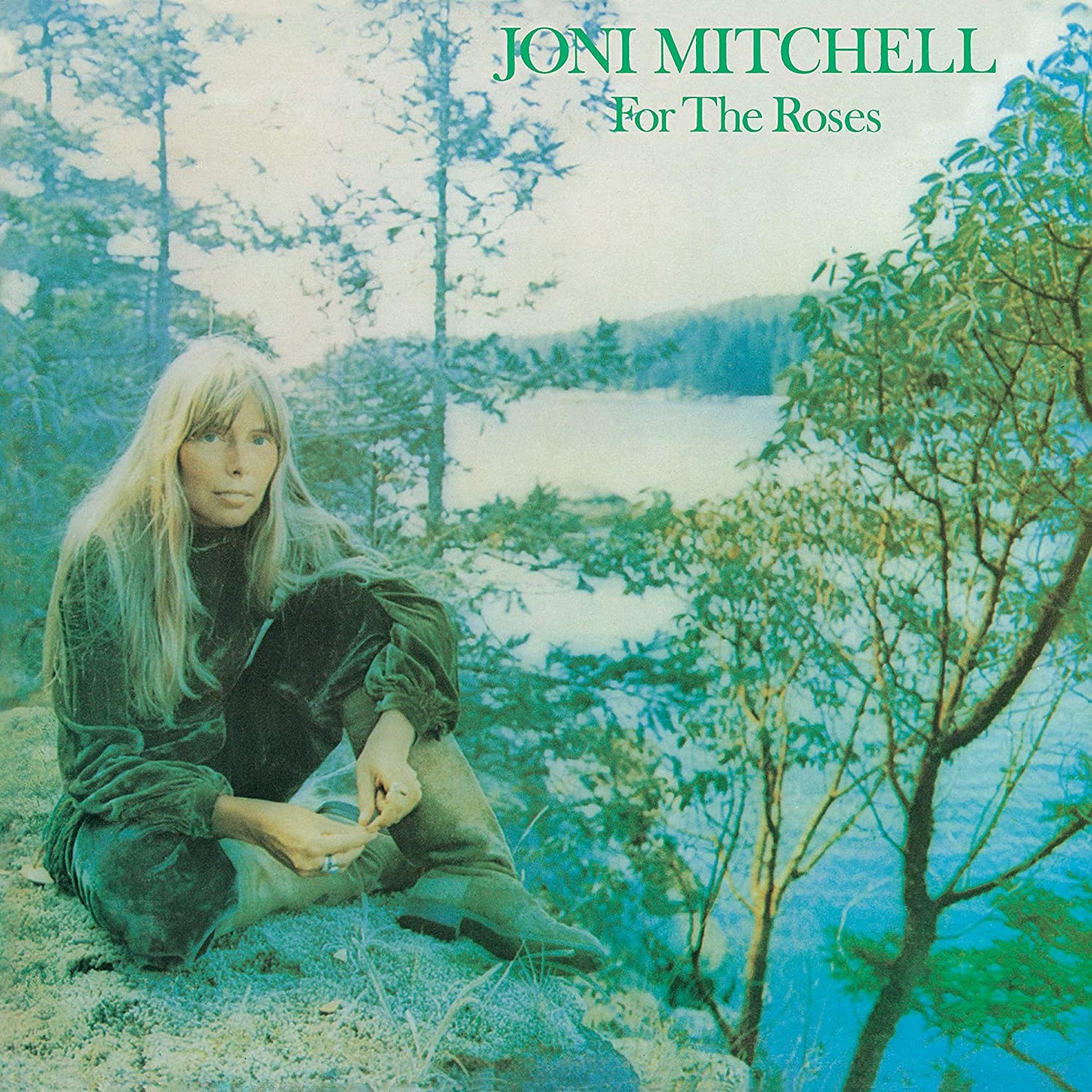

One night in the summer of 1972, Joni Mitchell walked outside of her austere, stone mason property she had just acquired in Sechelt, British Columbia, outside of Vancouver and well outside of the music business. She would sometimes try to tune into the latest musical act on Midnight Special, but she would often give up, walk out, think about where James Taylor must be—he had recently been, to use a Joni Mitchell word her lover--smoke, brood, and try to embrace the earth and think that there must be bigger problems than her emotions, though it was hard to tune into that. She would later say that she had been trying to quit the music business as soon as she got in it, that she was a painter that had somehow lost her way. And then life, as it often would, simply reached out like a painting on a canvas, like a Joni Mitchell song.

I heard it in the wind last night

It sounded like applause

Did you get a round resounding for you

Way up here

The previous year, at another moment in the crossroads, Mitchell made Blue (1971), which would eventually become her most well-loved album, the one people would own while knowing little else. Songs like “A Case of You,” “California,” and “The Last Time I Saw Richard” became touchstones of sorts, the ultimate album charting the lifecycles of relationships. If you have gone to the depths of Blue and gone no further, you may think there is nowhere else to go.

In the case of Joni Mitchell, there is. None of the songs on For the Roses are as well-loved or even well-known like the songs on Blue, but for those willing to listen and fully take it in, the songs, if it is possible, are even more demanding, formally and emotionally. The songs on For the Roses were written in her new Sechelt property, what she later called her Walden Woods. Although she would occasionally escape to socialize in nearby Vancouver, she was mostly alone in her idyll. Many of the songs were messages to James Taylor, with whom she had recently broken up after a rocky romance. “Blonde in the Bleachers,” “See You Sometime” and the title track about how this rock star thing would be a big letdown:

I'm not ready to

Change my name again

But you know I'm not after

A piece of your fortune

And your fame

'Cause I tasted mine

Just wait, James. “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire,” and allegory about heroin addiction, was also about James’s habit:

Concrete concentration camp

Bashing in veins for peace

Cold blue steel and sweet fire

Fall into Lady Release

"Come with me I know the way" she says

"It's down, down, down the dark ladder

The things that give us pleasure will bring us pain. Joni didn’t invent this, but she documented it with unflinching honesty, and her song about addiction entrances and makes you want to hear it again. In the title track of Blue, Mitchell said that even if hell wasn’t the hippest way to go, she still wanted to look around it. In “Cold Blue Steel and Sweet Fire,” she goes there, down, down the dark ladder. That song—flanked by Tom Scott on alto saxophone—was a preview for the LA Express accompaniment that was to follow on the commercial breakthrough of Court and Spark, but she wasn’t there yet. Her accompaniment is mostly spartan on For the Roses--subtle reeds and overdubbed vocals. There is nowhere to hide. You are hearing a gorgeous breakdown, a woman who tried therapy, drugs, relationships, and could only turn to herself and her songs.

Warning: If you are feeling depressed, this album could make you feel worse. Most people seek out pop music to feel better, but Joni Mitchell, especially on this album, is not there for that. She is there to give you something unflinchingly real. The stunning vocal runs, ruminative piano, and hypnotic guitar, make the misery euphonious, but this is an album for people who can handle the truth, and even though 1972 was a long time ago, the truths on this album remain just as painful and uncomfortable, maybe even more so.

In the middle of this crisis, there is a ray of sweetness, “You Turn Me On, I’m A Radio,” contrived to be the hit that David Geffen asked for, which stalled at 25. It still sounds like a hit—like the wind sounding like applause--it aims to please the way the rest of it is aimed to bum you out, and the reprieve reminds you of happiness for a few minutes, just to remember, as she already said: You don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone. That phrase from “Big Yellow Taxi,” a playful song with a serious message, would reverberate throughout For the Roses. Everything leads to the same place, a paved paradise, an earth that could never be saved, men to break your heart, mirages that turn out to be delusional. Those three waitresses in “Barangrill” aren’t really the trinity, and even if she tried to cheer up Beethoven in “The Judgement of the Moon and Stars,” the deaf stay deaf, the heart stays broken, and men will still fuck their strangers.

Joni really went there on For the Roses, and in many ways, it was the last time she could, at least the way she did it. Within a few years, her ability to sing long lines already became impaired by cigarettes and vocal nodes. She would continue to make emotionally demanding music, but she had to accommodate her voice to bring it across. Some people appreciated Joni’s voice as it changed, of course, but this moment of virtuosic disclosure would be the last of its kind. She bared all on this album, and the Botticelli inspired nude on the album’s inside cover—a Joel Bernstein photo—was her preference for the cover.

Her manager Elliott Roberts, talked her out of it: “How would you like 5.98 stamped on your ass?” On For the Roses, Joni Mitchell made a blunt rejection of the music business, but even she had her limits.

Probably my favorite album of hers. I was at a very difficult time in my life when it came out. In the Fall of 1972 I was 17, living in a psychiatric halfway house in DC, and my first love broke up with me right after we listened to it. And yet, in the depths of depression, it somehow uplifted me.

Thank you for the beautiful memories - both yours, Joni's, and mine.