Joni Mitchell's Resurrection Symphony

Carrion and Mercy and Another Stop on the Carousel

In the Summer of 2013, I went to Massey Hall to see Joni Mitchell headline a festival that had spent two days celebrating her music. Esperanza Spalding sang an exquisite “Dawntreader,” and Lizz Wright destroyed everyone with “The Wolf that Lives in Lindsay.” This was a festival for people who really love Joni Mitchell, who knew the words to that song. That week in Toronto was something of a dream. I hung out with a group of people I would never see again. We felt so close, and never kept in touch. And I caught a Laurie Anderson performance—all new material, no “O Superman.” Joni had sung a little in 2007—a short set with Herbie Hancock for something called Nissan Live Sets, then a two song gig later that year as a benefit, but something had happened in the intervening years. She was smoking about four packs a day of American Spirits, her vocal nodes were getting worse, her Morgellons Syndrome was ravaging her skin and possibly more. When the Olympics came to Vancouver—near her Sechelt property in the Sunshine Coast—and asked her to sing “Both Sides Now,” it broke her heart to pass.

So there I was—June, 2013. Herbie Hancock was on piano, Brian Blade was on drums, Bill Frisell was on guitar. Joni had talked to the CBC that week, and said she couldn’t sing anymore. She’d have to talk her way through. She had done a public interview with Jon Pareles of the New York Times on the University of Toronto campus—my parents’ alma mater—and she was asked to name a peak among many.

P: Is there a line of yours or a verse of yours that you're proudest of?

JM: I don't know if it's the best or anything but I'll tell you. The one that excited me when I wrote it... the most excited I ever remember was in "Furry sings the blues", the second verse, the second part, trying to describe this trip I took into this ghost town of the old black music, with wrecking cranes standing all around while the city fathers decided whether to keep it for historic reasons or not. And there were three new businesses on there, all aimed at black exploitation. Two black exploitation films in the New Daisy theatre, and two pawnshops.

JP: This is Beale Street that you're talking about.

JM: Right. The part that I recall being excited about language more than anything in all my writing, more than anything, was "Pawnshops glitter like gold tooth caps. In the grey decay, they chew the last few dollars off old Beale Street's carcass. Carrion and mercy. Blue and silver sparkling drums, cheap guitars, eyeshades and guns, aimed at the hot blood of being no one. Down and out in Memphis, Tennessee, old Furry sings the blues." Because it poured out almost in blank verse. It just kind of poured out, like, "Oh, girl, the Blarney's with you now.”

This thought must have stuck with her, because the night I saw her, in elegant funeral black, with her hair done like a 40s movie star, she began by talking about this song, telling one of the epic stories she told me, which sometimes took a long time, but usually had an Aristotelian irony baked in as a kicker in the end. She didn’t say it explicitly, but seeing Furry Lewis past his prime inspired a brimming Joni in her prime to describe the whole encounter, wrecking balls and all. The tourist goes to see a dead thing and takes pictures. Joni does not want life to be a travelogue of picture postcard charms. She wants real experience, a real story, something original. She can make it sound seductive but it’s the rude truth. She quoted Furry Lewis saying, “I don’t like you,” and she loved that. Lewis later threatened to sue Joni for her use of the line. Elliott Roberts, her manager, said, “If we had to pay everyone who said they didn’t like Joni, she’d be broke.” Joni realized that she wrote it when she was a 32-year-old on a creative peak. She was now approaching 70, and her voice that could once scale three octaves could barely rasp out what she called “three or four iffy notes.” As a young woman, it was audacity to take on the voice of a broken down old man, accompanied by Neil Young’s clangorous harmonica. Now her range had narrowed. Before she started singing, she crossed her fingers and looked up to whomever. After the first verse, she comically but honestly showed us that this was really hard for her. We cheered her on. At the end of the song, she improved some Furry dialogue. From his end, it sounded like Joni was trying to tell him that she didn’t play in standard tuning. “I can play in standard tuning! I don’t just play tunins’.” Brian Blade, playing exquisite drums, was cracking up. “I don’t like you,” she repeated. It was the last line of the song. Seeing Blade take pleasure in everything Joni was doing was a lifeline. The evening also included a spoken word performance from the diaries of Emily Carr and “Woodstock,” where she shared the stage with her daughter and everyone else who performed, so that she could share the burden of singing. She sang a couple of songs for a couple of nights, and I was told she had to go on vocal rest for a month afterwards. I thought this was the last time I would see Joni on stage. She played guitar for me in her kitchen a couple of years later, to prove a point about her perfect intonation.

That was seven years ago. When she had an aneurysm a couple of months after that encounter—in which we stayed up all night and talked about everything, then she called me to complain shortly after and we talked about more everything—and I got emails from nearly everyone I knew. One was from Leonard Cohen. Joni, who had spoken bitterly about him, melted when when I told her that he would love to see her at a place of her choosing. She told me the time window of when to catch her. She had no voicemail or machine, and the trick was to not wake her, but call before anything had gone wrong. Now Leonard was emailing me with a USA Today (!) story about Joni’s aneurysm. I asked him if he called her. “No, I never did call her,” he said. “Joni—so much suffering!”

But that was not the end of the story. This was the Joni who survived polio, who clawed her way through poverty while she was writing songs that would last forever. When no one would take a girl singer seriously as a writer, when she had to give up her daughter and a miserable marriage, who kept pushing until David Crosby, Mo Austin, and David Geffen—among many others—were all persuaded. After the aneurysm, when people were getting their obituaries ready, she slowly returned. After suffering the gravest health scare of her life, she did something she could never do for the rest of her adult life. She, surrounded by round the clock caretakers, gave up smoking. It must have been awful, but there was nothing she could do about it. Her second husband Larry Klein told me that every time Joni tried to pack it up, she was so impossible to be around, he eventually begged her to start smoking again.

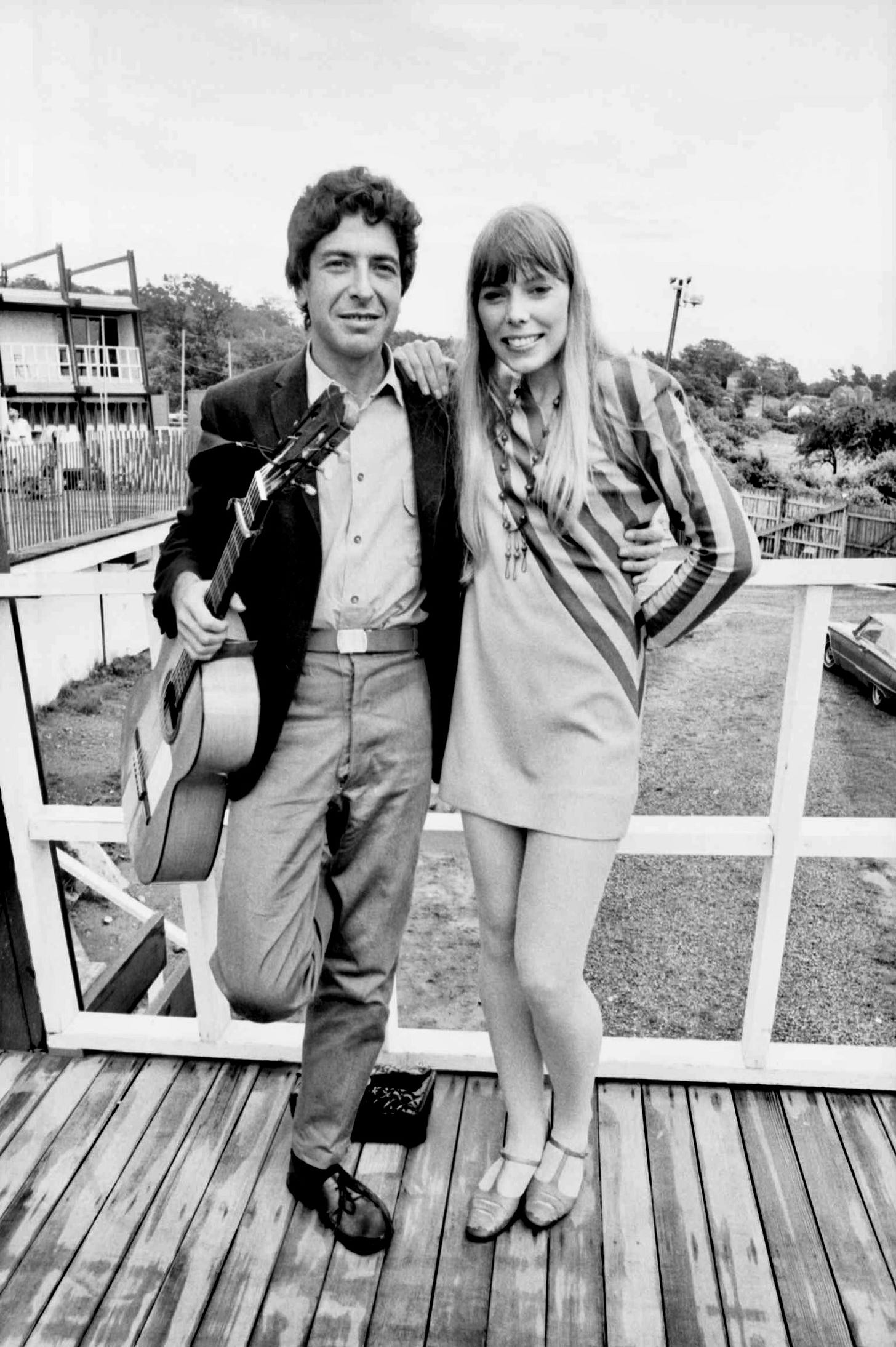

I had read of these jam sessions at Joni’s house. Brandi Carlisle—her most famous young exegete, who sang the Blue album in its entirety at Carnegie Hall—would be on hand at jam sessions at Joni’s house in Bel Air, where Harry Styles, Chaka Khan and others would sing jazz standards with her. There was a strict policy of checking phones at the door, so no recordings leaked. I wondered how Joni’s voice sounded after she had been cigarette free for the first time since she took her first puff at age 9. An afternoon billed as “Brandi Carlisle and Friends” was a covert comeback for Joni. They recreated the jam sessions in public, the first time she had played Newport since 1969. (The first time she played Newport, in 1967, she meet Leonard Cohen there. He was the one who told her, “I am as constant at the northern star.”) At first it took some coaxing. She became her own backup singer, letting Brandi Carlisle take the lead. And some of those songs are hard to sing. But by the time she sang “Both Sides, Now” and “Summertime,” and “Love Potion No. 9,” you could hear how her instrument had more clarity and flexibility than it had in a long time. She played “Just Like This Train” on guitar, just to show us that she could. She needed no help singing “The Circle Game,” a song that predated her first Newport performance. I find that as I age, it is harder to sing or even hear this song without tears. Life never quite follows the map of the song. It was written for a 20 year old, by a 20 year old. But as we age, we go back to it we are blown away. It was hubris for us at 20 to imagine ourselves at 40, or 50, or 60. Joni is nearly 80, and she could not imagine how much she would have to relearn at this point in her life. It’s like the Riddle of the Sphinx. What walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at mid-day, and three legs in the evening? The answer is “man,” but Oedipus gets it because he, walking with a staff, doesn’t fit the riddle.

And Joni doesn’t quite fit her own circle game. There is nothing about surviving polio or giving up her daughter. Because she didn’t fit the circle game, she had to write it. She was trying to cheer up Neil Young. Now she was giving herself a pep talk. She had a new voice to show off. In this vale of tears we have to live in, once in a while, a miracle happens. We’re captive on the carousel of time. We can’t return, we can only look. We can look at it right now. Joni had said that the muse of music had gone out for her, so all that was left was “ick.” Joni said a lot of things like that. But that’s not the end of the story.

David, Once more you add incomparable perspective to the incomparable Joni Mitchell. Bravo!

David, thanks for this installment! She’s not done! It makes me so happy. 😭