A Lifetime Burning in Every Moment

Sloth, Inspiration, and Taking Your Time Between the Notes

In the Summer of 2000, I was malingering in the most unproductive year of my adult life. I was an adjunct at Hunter College, writing theatre reviews for The Nation, making a few glossy diversions to keep the wolves at the door, and stalling on my dissertation. My advisor, someone I revered, told me that the only way to get an academic job was to write a boring dissertation, and this was something I could not bring myself to do. I was 27, old enough to be a dead rock star. I was at a power table at Birdland, reviewing a show by Jimmy Scott for the still intact Village Voice. On one side was my good pal Joe Hooper, who wrote a New York Times Magazine feature called “The Ballad of Little Jimmy Scott.” On the other side was my beloved mentor Wayne Koestenbaum. I had an independent study with him a couple of years earlier, and his muse loomed large for me as I was attempting what felt like an improbable climb. He was constantly making things—poems, essays, books, fashion theory, and more as the years went on. He was always trying something new and made me feel like I should, too. It is lovely to be a professional fan and I was, and is, a fan of his.

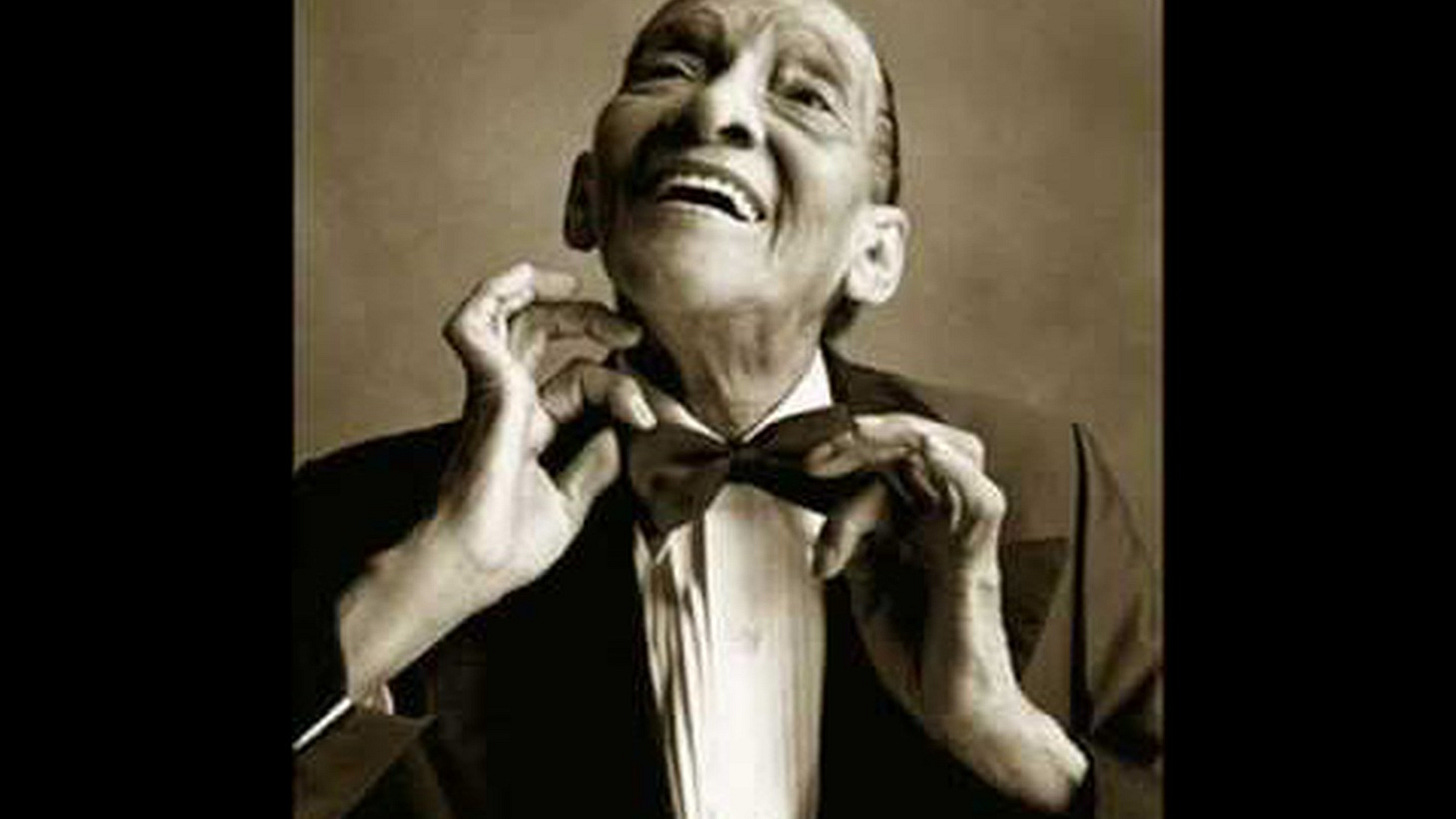

Scott had an unusual ailment, Kallman Syndrome, that arrested his puberty and gave him the closest thing you could have to a voice that could be called nonbinary--way before that term was in the water supply. Early in his career, when he was 4 feet 11 inches, he was known as Little Jimmy Scott. He shot up to 5 foot 7 after turning 37. Now he was the Legendary Jimmy Scott. The first time I heard him singing “Embraceable You,” I asked, “Who is she?” An innocent mistake, but it was a kind of post-gender aesthetic.

Lou Reed put Scott on Magic and Loss, on a song called “The Power and the Glory.” “I wanted all of it, not just some of it,” he sang with everything he had an octave over Reed’s baritone drone. The album was an extraordinary meditation on. death and dying—and Scott, more than 20 years older than Reed, provided the vitality. David Lynch put him in the final episode of Twin Peaks. Madonna—Madonna!—said he was the only singer who could make her cry. His only legit hit “Everybody’s Somebody’s Fool” was in 1950. It was a long way to the top. But what really knocked me out was the way he took his time. He made room between every beat for a lifetime burning in every moment. Wayne said to me, “It was as if he was saying, let’s leave hitting every note to the kids.”

Ethan Hawke and Uma Thurman were among us. And while I sat there decidedly not writing a deliberately boring dissertation, as I was taking my time, I thought about Scott taking his. Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies” is, depending how you play it, the epitome of ebullience or, if you slow it down, a heartbreaker. Musically, it is not sunshine. It is a descending minor chord with a melody that can be torn apart, sung backwards or forward, or sung straight out. There’s something about celebrating life “when you’re in love.” When you’re not in love with the world, “Blue Skies” bears the weight. I saw an eternity go by between syllables. Jimmy Scott was 75. He had been at this a long time, and knew about disappointment, sucking it up, and delivering something real. He was not going to write a boring dissertation.